Stella Terra, Solar Team Eindhoven’s (STE’s) 4x4 sun-powered concept car has completed road testing in Morocco and was demonstrated live at Intertraffic Amsterdam in April 2024. But are cars powered by the rays of the sun really the future of mobility?

Stella Terra doesn’t look like any vehicle you’ve ever seen, with a wider, longer bonnet and roof to accommodate greater surface area of solar panels, a lightweight frame and fiberglass chassis, an aerodynamic profile and low ground-hugging design.

STE technical manager, Bob van Ginkel is not long back from the Sahara, where the 4x4 Stella Terra finished its test run over 1,000km (621 miles) of difficult and varied terrain. The team is composed of 22 T/U Eindhoven students who took a year out to work on the Stella Terra, none of whom had built a car before.

“The mood was very good in the team,” says van Ginkel. “We were so excited that we were able to complete the journey completely on the power of the sun, and we even had a lot of energy left in the battery.”

Next stop for the Stella Terra was Intertraffic Amsterdam, which took place at Amsterdam RAI exhibition centre in April 2024. It’s much closer to home than Morocco – it’s just 119km from the T/U Eindhoven campus where the vehicle was built.

We aim to inspire everyone to accelerate the transition to a sustainable future. We encourage the markets and individuals to accelerate that future.“ Bob van Ginkel, technical manager, STE

Plans are afoot for a VIP to be riding in the car for this auspicious journey, as part of an initiative to raise awareness of the EU’s commitment to SEVs and the future of electric mobility.

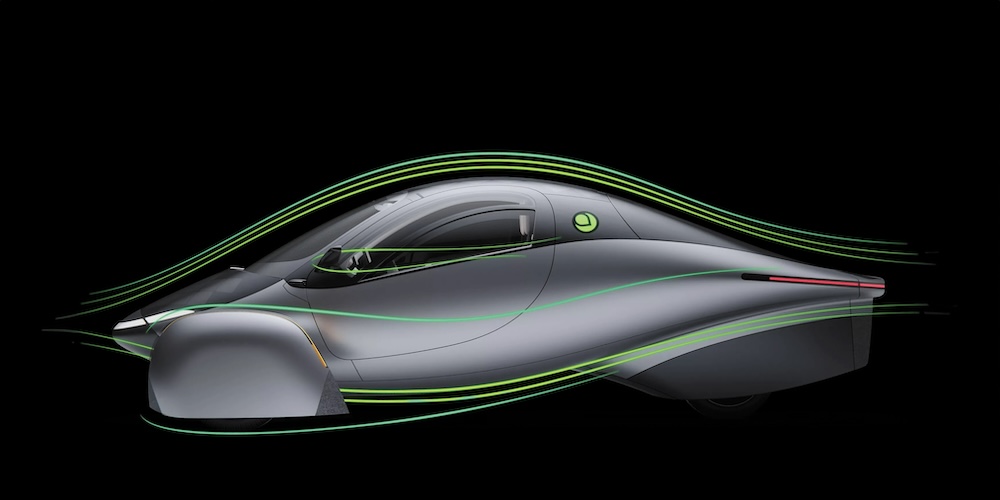

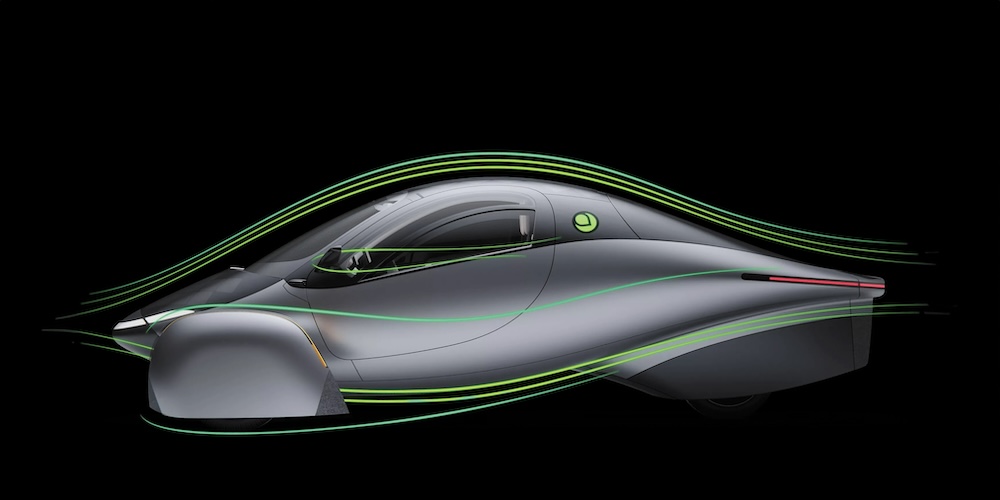

The design

Many of the Stella Terra’s components are built from scratch, for optimum performance. For instance, its solar converter is 97%-efficient, with the panels themselves achieving a respectable 24.4% efficiency.

“We needed to make the car very lightweight,” says van Ginkel. “It needed not only a low rolling resistance – the amount of energy you need to go forward – but a minimal amount of drag.”

The low air resistance is achieved by a distinctive aerodynamic design, that tends towards the ideal ‘teardrop’ shape, while balancing the need for as great a surface area as possible available for solar.

Solar panels built in to the bonnet and roof can be further augmented by panels stored within the vehicle and assembled onto the sides and back while stationary. This gives 16m2 of solar panel area. The back panels also raise in a pop-out roof, which provides a better angle for capturing sunlight.

Rather than a steel chassis, Stella Terra has a fiberglass frame. The weight savings are immense; fiberglass is about 1,500-1,800kg/m3 versus steel which is 7,850kg/m3.

The battery has a mere 60Kwh, a lot less than comparably sized EVs, and this is one of the many elements that helps keep the weight down.

The Stella Terra is less than half the weight of similar sized 4x4 EVs. The BMW Xi for example is approximately 2,500kg, while the Stella Terra weighs in at 1,200kg. Its top speed is 145km/h (90mph) and it has a daily range of 708km (440 miles) on-road, and 548km (341 miles) off.

Watt’s in a wheel?

Stella Terra’s off-road capability is in large part due to its in-wheel motor design. Rather than a central electric motor running by driveshaft to four wheels, each sports a Protean pd18, which has 80kw of peak power, 1400Nm of torque, and weighs only 9kg – for a total of 36kg. Each is a very compact 43.3 x 12.5cm.

This design gives further weight savings, as it forgoes an extremely heavy component: the driveshaft. The brakes are integrated and it’s also direct drive, which means no gears, so yet more weight reductions.

“In-wheel motors really shine for solar vehicles because they reduce the weight of the vehicle,” says Luka Ambrozic, chief commercial officer at Elaphe, which supplies in-wheel motors for another Dutch solar car, the Lightyear. “They increase the space available, which helps in making the vehicle more aerodynamic.

“They are also very efficient. Much more so than any ICE equivalent. They’re much better optimised for long range cruising at highway speeds.”

But there are trade-offs involved. The weight of the motors is not born by the vehicle’s suspension, but by the wheels themselves.

“It’s unsprung mass, which means you add weight to the wheel,” says Ambrozic. “This means that the ride is, in theory, less comfortable. But that is largely manageable.”

Another issue is the currently higher cost. “It’s a new technology,” says Ambrozic. “Typically, we’re not dealing with the components that have been cost optimised for the last 50 years.”

The cost of solar

The Lightyear Zero came in at €250,000 (US$270,000), although as a proof-of-concept this does not necessarily reflect the final cost of SEVs, which might, when fully mature, have a lower overall cost due to the smaller battery.

The Lightyear Zero has a drag coefficient of 0.19, and a 60Kwh battery gives it a range of 625km (388 miles) before the solar element is added, with a further 40-100km range extension per day, dependent on weather.

In the EU, only one in five workers have a commute higher than 30km (19 miles). So this would place charge-free driving in the hands of the majority.

Only a few of the pre-orders made it off the assembly line, and for financial reasons, focus has shifted to the more affordable Lightyear 2, priced at €40,000 (US$43,000).

“If you’re looking to build a solar car for the masses you need a low cost technology,” says Luka.

Teething pains

Arval, owned by BNP Paribas, placed a 10,000 unit order for the Lightyear 2, calling the technology “proven, affordable and environmentally friendly.”

But Atlas Technologies, the operator of the Lightyear startup, was forced to declare bankruptcy in January 2023. Nevertheless, parent Atlas Technologies Holding is still solvent and owns the IP, which has allowed Lightyear to reboot, with the intention of eventually fulfilling preorders. They are now also focusing on manufacturing solar bonnets for mainstream OEMs.

Elsewhere in the burgeoning SEV industry it’s a similar shaky picture, with Sono Motors, the builders of the Sion solar car, filing for insolvency in May 2023; and Aptera, creator of a futuristic three-wheeled solar buggy, only resurrected in 2019 via crowdfunding, having been declared bankrupt in 2011. As of June 2022 Aptera was said to have over 22,000 orders on its books, but still no word on whether production has begun in earnest.

None of these are large, well-funded OEMs, but rather enthusiastic startups attempting a mammoth project, with an extraordinary variety of entirely new parts to manufacture. They rely on angel investors, community crowd funding, and pre-orders as well as conventional finance.

The difficulties haven’t been due to any underlying issue with the technology, nor for lack of enthusiasm by backers, but rather the challenges in producing a whole host of novel or underused components without the developed supply chain of the big OEMs.

Future design philosophy

What’s clear is that the likes of Stella Terra and Lightyear are not simply EVs fitted with solar panels. Rather, achieving viable SEVs means rethinking the car concept from the ground-up. At each stage of the process, every component has been optimised for weight and efficiency.

“The Stella design philosophy is to build a car that consumes as little energy as possible in manufacturing, but also needs as little energy as possible to drive,” says Van Ginkel.

There is already a small and highly motivated network pushing forward this lightweight, energy-efficient paradigm.

“The vehicles really need to be designed in a holistic way,” says Ambrozic. And he is certain that this design philosophy has a lot to offer the wider industry.

“What emerges is just how inefficient ICE vehicles, and even the latest EVs are compared to the ceiling of potential, which is currently being pushed by solar vehicles. The efficiency gains will of course have huge impacts outside the SEV market,” says Ambrozic.

Green impact

Concept cars such as Stella Terra show that the solar vehicle project is feasible – but the struggles of the commercial sector illustrate the scale of the task.

“Overall, if the vehicle provides good economics, everyone will drive them. It’s a simple equation of what’s your total cost of ownership in the end,” says Ambrozic.

And with fuel costs of zero on a sunny day, the benefits are certainly enticing.

“But it is more of a matter of time. And maybe some integration challenges that arise with increasing use,” says Ambrozic.

SEVs have the potential to accelerate the journey to net zero because the availability of charging infrastructure ceases to be a limiting factor, especially important for the most densely populated cities and the most remote rural locations.

“We aim to inspire everyone to accelerate the transition to a sustainable future. We encourage the markets and individuals to accelerate that future,” says van Ginkel.

And Luka Ambrozic is also emphatic about the importance of the mission.

In reality, we’re not saving the planet, we’re saving the human race – our children and our children’s children.

This article was first published in Intertraffic World 2024