Who’s on your kerb?

The pandemic has put pressure on kerb space like never before, with more delivery drivers servicing the e-commerce boom, more active travel options requiring docking spaces, outdoor seating and pedestrianisation seeing a surge in popularity, and private car-use, with associated parking needs, on the rise. Enter a new era of smart kerb management – and with it the tools to provide a nudge toward vehicle electrification

In August 2021 US president Joe Biden made headlines after issuing an executive order demanding that half of all new vehicles are zero emissions by 2030.

It was big news in a country where EV uptake still lags behind the two main markets of Europe and China (according to the most recent International Energy Agency figures, the US has 1.74 million plug-in electric cars on its roads compared to three million in Europe and 4.6 million in China.)

Alongside the executive order the Biden administration also announced US$60 million-worth of grants through the US Department of Energy (DoE) to fund projects aimed at decarbonizing the US transportation sector.

One of the grants was a US$4 million award for ongoing funding for a pilot project aimed at incentivizing EV use in three US cities - Los Angeles, Santa Monica and Pittsburgh.

In February 2021 Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator (LACI) and the City of Santa Monica launched and deployed a first-in-the-nation Zero Emissions Delivery Zone

The project, “the most comprehensive of its kind” yet to be tried in the US, according to Ariana Vito, the electric vehicle program coordinator for the City of Santa Monica, hopes to push EV uptake through kerbside management policies.

It will do this primarily through the creation of dedicated zero-emission loading zones for commercial vehicles. The selection of the three cities was deliberate, notes Erin Clark, the autonomous vehicle policy analyst of Pittsburgh Department of Mobility and Infrastructure. These are all cities with historically poor air quality,” she says.

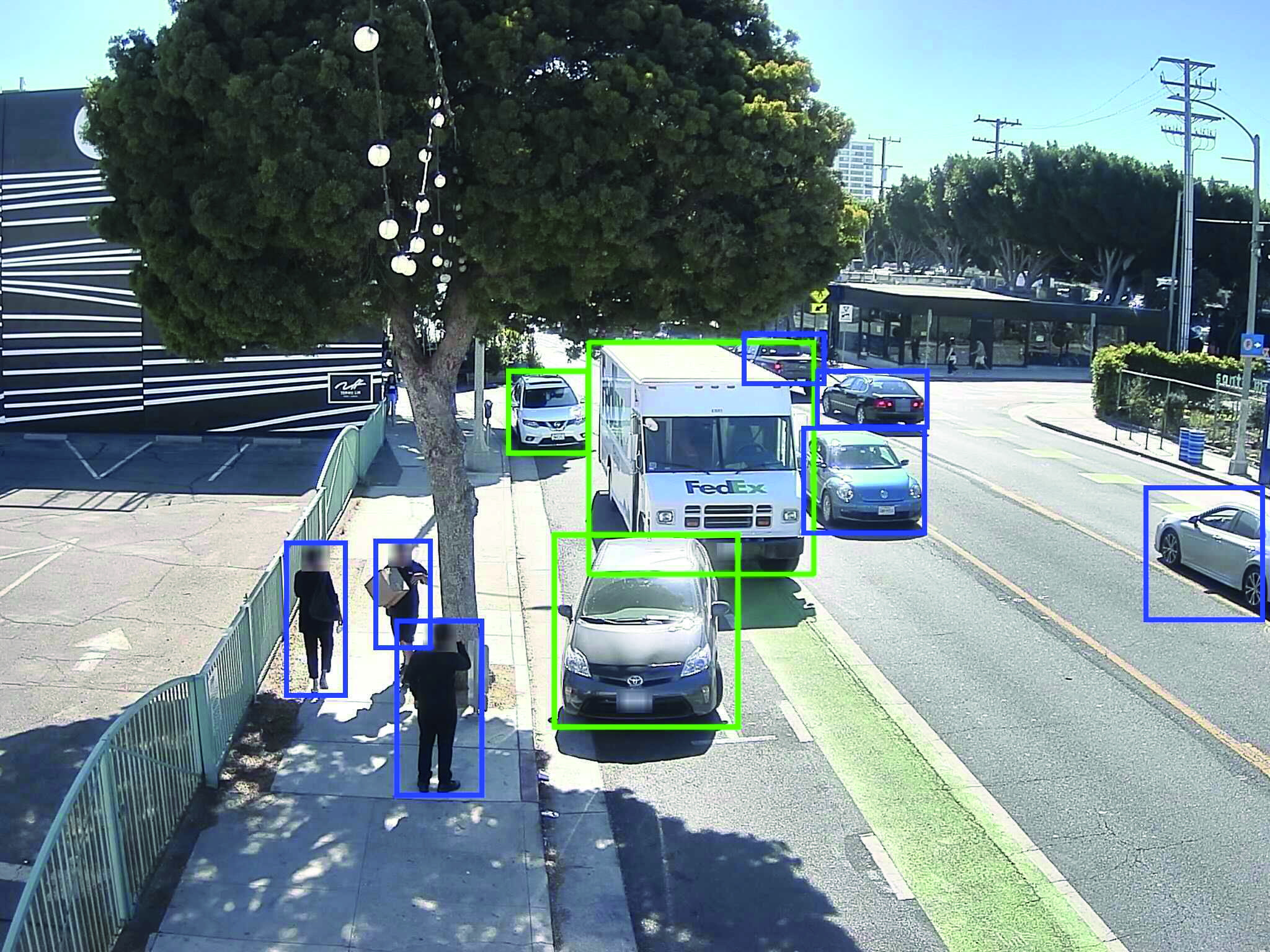

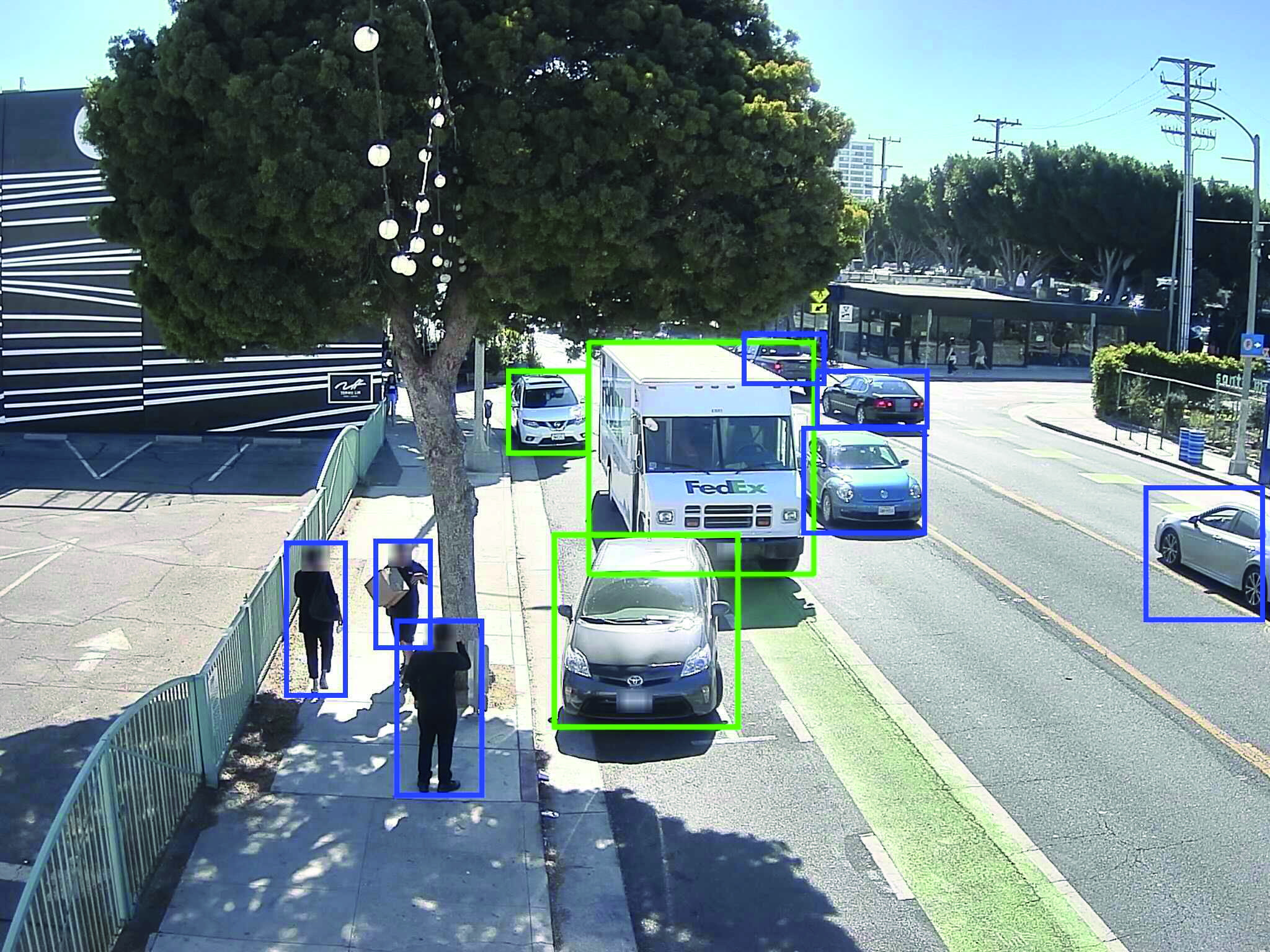

Computer vision

The three cities are working with a number of technology partners, including several US universities. However, integral to the success of the project will be the deployment of technology developed by the computer vision start-up Automotus.

Automotus’ tech works by deploying “cameras as a data source to tell cities how different types of vehicles are using the public right of way,” comments CEO and co-founder Jordan Justus.

The Santa Monica kerbside management programme will include local delivery firms

The company’s software can verify how the kerb is being used as well as the types of vehicles parking there by leveraging machine-learning and AI to identify a vehicle’s make and model. This means that it can know immediately if the parking vehicle is zero-emission or not.

While this may eventually be used for the purposes of enforcement, Justus believes that for the early stages of the pilot the camera technology will only be used to understand how the kerb is being used.

“Historically the kerbside has been used for on-street parking for passenger vehicles but that's not how it's being used anymore,” says Justus. “So we want to help cities first understand what's actually happening on the ground so that they can then use the tools at their disposal to change driver behaviour.”

Pilot projects

The first pilot is already underway since early this year in Santa Monica, Los Angeles County’s famous beach-front city. Prior to it going live a suitable place to host the pilot needed to be found in the city’s downtown, notes Vito.

In February 2021 Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator (LACI) and the City of Santa Monica launched and deployed a first-in-the-nation Zero Emissions Delivery Zone

Vito explains: “We selected a one-mile pilot zone within our downtown area where we have the highest concentration of deliveries, and then scouted different available kerb spaces within that specific area.”

We selected a one-mile pilot zone within our downtown area where we have the highest concentration of deliveries, and then scouted different available kerb spaces within that area’- Ariana Vito, electric vehicle program coordinator, City of Santa Monica

Through this process 11 zero-emission loading zones were selected and fitted out with Automotus’ camera technology. The city also spent several months of outreach to “surrounding retail businesses that could potentially benefit from the spaces,” says Vito.

They also contacted a number of delivery companies to see if they would take part. While the response was lukewarm from the big players in the field such as UPS and Amazon (“they were unwilling to commit to the data sharing requirements,” says Vito) a number of smaller-sized companies have come on-board.

They include the produce delivery company Perfectly Imperfect Produce, the linen delivery firm Alsco and the yerba mate herbal beverage company Guayaki.

Besides delivery companies, the city has also teamed up with a number of tech companies including Fluid Truck, a truck sharing platform that has agreed to make available its small fleet of zero-emission trucks to delivery companies operating in the Santa Monica downtown.

The Pittsburgh pilot, meanwhile, was set to launch in early November and will run for an initial 12 months, according to Clark. Like the Santa Monica pilot it will begin with an outreach phase to local businesses and delivery companies in the city.

This will be followed by “an education phase,” says Clark. “What that will look like will be installing signage on the poles near those zones to alert drivers and the public that smart loading zones are coming to this location. It won’t be until the latter half of the pilot that we'll be attempting to do any enforcement.”

Kerbs are monitored using lamppost-mounted cameras

The same is true in Santa Monica where the city council will need to approve an ordinance allowing for the ticketing of non-EVs parking in zero-emission loading zones. “We aren't authorized within our municipal code to issue citations for this new type of zone,” says Vito.

What kerbside management policies ultimately wind up being adopted long-term by the cities involved the pilot is yet to be decided, according to Justus.

Enforce or charge?

One possibility being looked at is a move away from an enforcement parking model to a payment model, whereby EVs pay for access to the loading zones.

While asking delivery companies to pay for parking that they have traditionally accessed for free may seem a difficult sell on the surface, Justus points out that delivery companies are already paying cities large amounts in fines for parking violations every year.

In New York City, for example, UPS pay millions in parking tickets annually, says Justus. “What they typically do is come up with some sort of agreement with the city to pay a percentage of those tickets,” he says. “What we’re saying is, let's transition that account from citations as much as we can over to getting people to pay for their fair share of space, and then giving them enough space to where they don't have to double park.” Or as Clark puts it: “This is a way to create more predictability.”

Automotus’ camera technology can identify delivery trucks occupying the loading zones by reading their license plates, with the payment automatically charged to the delivery companies account with the city. Non-EVs that use the zero-emission zones could be charged a premium.

The price is right?

We can use the model to determine what is the optimal pricing to reduce congestion levels’- Sean Qian, professor of civil and environmental engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh

Finding the right pricing model will be key to making such a system a success, says Sean Qian, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh.

To do this Qian and his team are pulling the Automotus kerbside data currently being collected in Santa Monica and later in Pittsburgh and Los Angeles, and feeding it into computer models. The simulations use insights from behavioural science to predict how driving habits change when pricing is introduced at the kerbside. “We can use the model to determine what is the optimal pricing to reduce congestion levels,” comments Qian.

The pilot project authors see reducing congestion as an important secondary effect of the zero-emission zones because of the correlation between congestion and emissions.

A 2010 study by the University of California Transportation Center (UCTC), for example, found that CO2 emissions could be reduced by up to 20% through the use of congestion mitigation strategies.

The pilot project will focus on commercial vehicles rather than private vehicles because

this is the area of most concern for city parking departments, says Justus.

“Right now cities have such an under-served problem with commercial vehicles and that is where their biggest focus is,” says Justus.

Covid pressures

One of the main reasons this problem has arisen is because of a rise in commercial vehicle volumes brought on by the growing trend for online retail, Justus notes. This trend has been exacerbated during the last year by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, with city center restaurants in particular experiencing a sharp rise in food deliveries.

The result of this, according to Justus, is that “there are a lot more commercial vehicles fighting for kerb space.”

Alongside this spike in delivery operations there’s also been growing competition for kerbside access from other sources, says Clark.

“The demand for kerb space has changed a lot in the last few years,” says Clark. “It’s not just demand from commercial vehicles and for resident parking. We also have demand for bike lanes and – since the pandemic - demands for outdoor dining space.”

The demand for kerb space has changed a lot in the last few years. It’s not just demand from commercial vehicles and for resident parking. We also have demand for bike lanes and – since the pandemic – demands for outdoor dining space’- Erin Clark, autonomous vehicle policy analyst, City of Pittsburgh Department of Mobility & Infrastructure

According to Justus, many US cities have failed to keep pace with these changes. “The existing systems and real estate just don't align with the needs of commercial vehicles,” he says. “There's not enough real estate allocated for them. Meanwhile, the systems for payment, enforcement and data collection don't work.”

This article is part of the Intertraffic World Magazine.

View the digital version of the magazine here.