Mobility hubs are a growing sight on Europe’s streets. Dedicated locations where a range of sustainable transport modes are co-located in close proximity, bring far more benefit to society than just a place to park a bike and rent an electric car.

What is a mobility hub?

The concept of the mobility hub is not as new as the term might suggest. What is new is the fresh emphasis placed upon them over the last few years by local and national governments as the authorities seek to solve a number of problems with a single solution.

In 2020 Arup published a 38-page Mobility Hubs of the Future report that began with the definition of a mobility hub as: “In the current transport system, mobility hubs are commonly seen as physical places that connect a variety of transport modes. A mobility hub can be anything from a bus stop and a bike sharing station to an inner-city main train station.”

In the previous year the University of British Columbia published a white paper, Identifying Best Practices for Mobility Hubs, that also set out to initially define what a Mobility Hub actually entails. Says author Saki Aono:

“Mobility hubs are presented as a strategy to enhance sustainable and active modes of transportation through a user oriented lens in dense urban centers. Preliminary research regarding the definitions of mobility hubs helped inform the objectives of mobility hubs that can address core transportation needs and help guide their development.

These resulting objectives are based on existing…themes that improve travel experience through safety and place-making initiatives, embrace future changes through flexibility, support sustainable transportation options, and allow for partnership opportunities in the transportation realm.”

CoMoUK, the national organisation for shared transport in the UK, a charity dedicated to its public benefit (we hear from chief executive Richard Dilks later in this article) published introductory guidance to such hubs in 2019 and accreditation standards in 2020. They define a mobility hub as bringing together public transport, shared transport and active travel option(s) in a way that improves public realm.

So, we’ve established what a mobility hub is, at least, but what impact do they have on the lives of their users and of what benefit are they to society, not solely to mobility and transportation?

In the UK, “interchange” hubs have been part of commuters’, shoppers and sports fans’ lives for decades, although not necessarily consciously. Even the most basic of examples, a bike rack at a railway station is, in essence, a mobility hub but perhaps a better example, although still a simple one, would be “park and ride” scheme is an entry-level mobility hub that serves thousands of people and indeed serves its original purpose perfectly.

Park & ride: the original mobility hub

Here’s an example. A historic town centre has insufficient space for the thousands of parking spots it needs: the local council build a car park on the outskirts of the town and operate a park and ride service that sees visitors and shoppers leave their cars for a few hours and catch a special bus service that takes them, uninterrupted, to the town or city’s historic centre. And back, of course.

Very little technology is involved, other than perhaps a real time passenger information system, but nonetheless it’s a mobility hub, a place where two modes of transport meet for the purposes of multilevel convenience, reduced congestion, and significantly decreased vehicle emissions from traffic circulating around the city or the facility looking for parking.

Now, however, things have got a lot more interesting as mobility hubs become smart mobility hubs and eMobility Hubs, encompassing far more than just a secure car park and a convenient “hopper” bus. Smart mobility hubs are more multimodal than that – e-bikes, e-scooters and other shared microtransit options are now all part of the family, as Intertraffic discovers.

eHUBS Project: Shared green mobility hubs

The importance of mobility hubs to Europe’s transport thinking is underlined by the size and scope of its hub-related projects. eMobility Hubs (in short eHUBS) represent a “crucial step towards the adaption of shared and electric mobility services.” At the heart of the project’s goals is that eHUBS provide a viable alternative to the private car by “providing opportunities to increase shared and electric mobility in a truly innovative way.”

The project features six partner cities from five countries (Amsterdam, Arnhem (both NL), Dreux (FR), Inverness (SCO), Leuven (BE) and Manchester (ENG)) will promote eHUBS and pave the way for others to follow in their footsteps. The eHUBS implementation approach will differ according to the size and needs of the respective cities.

The project’s targets are clear, says the project’s press office: “By kick-starting the mobility transition in six pilot cities we will set an example for other cities in Europe, which will be able to benefit from applying the blueprint and copying best practices. A large-scale uptake will cause a leverage by significantly reducing CO2 emissions in the cities and creating a growing market for commercial, shared e-mobility providers,”

New concept in Flanders: “Mobihubs”

Another mobility hub-centric project was launched in September by SHARE-North project partners Mpact and Autodelen.net. Mobipunten, focused on the Flanders Region, will see mobility hubs provide bespoke opportunities for shared, sustainable mobility services.

Project partners Bremen and Bergen are already firmly established flag-wavers for the mobility hub concept - Bremen began its hub journey as far back as 2003 – and those two cities inspired the creation of similar schemes in Belgium.

A “mobipunt” is a transport hub based at a neighbourhood level where “To be truly effective, a city (or village) should have a network of several mobility points,” a project spokesperson explained, before highlighting an important aspect - localism. “In order to integrate these hubs into route planners, the Flemish ‘mobipunt’ concept suggests that every mobility point has its own name which clearly refers to the neighbourhood in which it is located.”

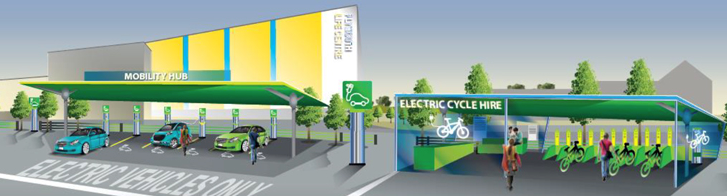

Source: CoMo

Autodelen.net and Taxistop (now Mpact) also published a collaborative white paper on what constitutes the ideal community-driven mobility point and continued the theme of bespoke, local installations. “In a perfect world a mobility point would also provide a meeting place for neighbours, a little neighbourhood store, a locker to deliver packages or store a bike helmet away while using a shared car.”

Bremen: Mobil.punkt, the first word in mobility hubs

Ask a selection of European smart transport experts which city they think is leading the way in terms of mobility hubs and it’s unlikely that the German city of Bremen won’t be mentioned. An inspiration for Flanders’ aforementioned Mobipunten, Bremen first embraced the concept of the “mobil.punkte” (or “mobility point”) 18 years ago. This was long before Rebecca Karbaumer began her tenure as Project Coordinator at The Ministry for Climate Protection, the Environment, Mobility, Urban and Housing Development, but she is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the mobility hub sector.

“When I advise other cities who call me and say, ‘Oh, we've heard of these mobility hubs and we want to do them’ my first question is always Why? Why do you want to do mobility hubs because mobility hubs should be a means to an end. In Bremen, Mobility hubs have always been and will always be a way for us to reduce private car ownership and to reduce parking pressure in the public realm, and then to reclaim public street space,” she explains.

“That's how it started in 2003. And it’s under that strategy that we continue to plan mobility hubs. Our mobility hubs focus on car sharing as a pillar of sustainable transport just like walking, cycling, and public transport are. The combination of all those modes reduces reliability on private car ownership.”

Cities can build their mobility hubs around any mode that fits their users’ needs, but as Karbaumer further elucidates Mobil.punkt is undoubtedly all about getting people out of their own cars. “With car sharing, an increasing network density of car sharing, and the accessibility, availability and visibility of car sharing, we're bringing a viable alternative to private car ownership closer to the citizens. Essentially Mobil.punkt sites are on-street car sharing stations with clear signage, clearly marked, clearly visible, easily accessible on foot or by bicycle. They always feature that signage and they always feature bicycle parking as one of the ways to encourage cycling.”

Karbaumer’s enthusiasm for her work is palpable, as can be evidenced in a recent webinar.

“The larger hubs are linked to public transport - tram and bus stops and in some sites, also taxi stands. In some other neighbourhoods the future will also see the addition of cargo bikes to some of the larger mobility hubs where we have the space available, plus parking zones for the free floating micromobility options, such as bikesharing and electric scooters, because those are fairly new on the market. We see the need to reorganize the public space around those shared travel modes as well.”

“I want to create a sustainable future. But it needs to be effortless for it to work for the mainstream. It needs to be easily accessible; it needs to be convenient. The benefit for day-to-day life has to be clear, and if you have that flexibility and freedom of choice for the services think it's a positive result for everyone.”

Mobility hub accreditation: credit where it’s due

Richard Dilks is chief executive of CoMoUK, a charity founded for the public benefits of shared transport and arguably the biggest supporter and proponent of mobility hubs in the UK. CoMoUK (formerly Carplus Bikeplus) runs accreditation schemes for car club and bike share operators that provides assurance to local authorities on a set of standards expected by service providers.

“We're not defined by a mode, which is helpful because if we're going to tackle decarbonisation and socio-economic inclusion challenges around transport, then bringing sustainable modes together is going to be more and more important. And that might sound obvious, but the reality is they're not brought together very much on the ground at the moment. The private car, inherently, bring things together so that's our competitive challenge,” he explains.

“Because while I think there will have to be measures that restrain private car use, there's a big issue here about attracting people into sustainable transport options.”

The benefits of mobility bubs to the travelling public are one thing, but who benefits from CoMoUK’s innovative accreditation scheme? “Accreditation is basically a ‘quality mark’ for mobility hubs,” he responds. “It's to give some definition, to stop the downside of reinventing the wheel! It gives interested parties a yardstick, a comparison, so it means you won’t have to dive in blindly and it gives people something to aspire to.

“We have a lot of people, public and private sector, even a couple in the third sector, having a look at mobility hubs, so it's designed to be helpful to them in the thinking stages, and gives them the next level of detail on from our intro guide in 2019, which was a typology of six different types of hub, different ways of thinking and also a way of raising awareness of the fact that this isn't just about urban or suburban locations.”

Within the next 18 months to two years, CoMoUK expects the number of mobility hubs to have significantly increased. As Dilks says, quite a number are in the process of being built with plans of one installation in England and another in Scotland, in addition to the first CoMo-accredited hub in South Woodford in East London.

Mobility hub ownership

And what about ownership: whose mobility hub is it anyway? “In the UK pipeline alone, we are already seeing a variety of answers. Some hubs will be wholly or mostly owned by the public sector; others will be wholly private sector owned; others still will adopt a hybrid ownership model. Many will transition from one model to another over time – most commonly from public to private ownership. In terms of revenue generation, the answers will vary from site to site, so having some degree of flexibility will be really important.

“One of the most important lessons we learned from the development of mobility hubs in Europe is to start small. The smaller the hub, the lower the risk.”

All of which helps to explain why we at CoMoUK are moving on from simply advocating for the concept of mobility and community hubs to offering an accreditation service. Moving forward, we will offer assessments of mobility hub components against our criteria, which will vary by location type. Eventually, we hope to twin our accreditation work with analyses of the business, ownership, revenue and viability models that underpin mobility hubs and shared transport more broadly.”

Freight Hubs – the next generation

Also lighting Dilks’ fire is the prospect of freight mobility hubs, an expansion if the idea of the pick-up and drop-off lockers operated by the likes of Amazon. “The next level from the locker is a hub for cargo bike freight operations. And all those schemes are starting to burgeon, which is really exciting. Things like are really gathering some pace. And we've just seen two ecargo bike share schemes get going in the UK in Hackney and Manchester. I think they are a really interesting crossover.”

Could some of these hubs be the microdistribution hubs that those operations and operators need? “While there are lots of positive knock-ons about reducing diesel emissions and reducing motorized freight traffic in an area, it's not actually all that simple to do, because you may be building an extra cost or complexity into quite a fragile, very price-sensitive supply chains. So there's a lot to think through there. It's not just going to magically happen; it needs co-ordination. But it is important it does happen.”

Mobility hubs may have come from relatively humble beginnings but as can be evidenced above, they are becoming an ever more important and forward-thinking facet of a city’s transport offerings.

Mobility hubs: Four examples of a shared mobility future

Berlin: fuelling the mobility hub debate

In central Berlin, a new mobility hub is set to become the blueprint for the bp fuel station of the future. The hub is an “important step” in bp\s strategy to offer convenience and mobility solutions that will help the company achieve net zero by 2050. The hub features:

- A conventional Aral station with REWE To Go Shop.

- A battery changing outlet for e-bikes, cargo bikes and small vehicles.

- Car sharing in several partnerships.

- e-scooter sharing.

- Bike sharing.

- Two Aral ultra-fast charging stations.

- Connection to public transport (S-Bahn/U-Bahn/Bus).

The hub even has a DHL parcel connection facility and offers customers a comprehensive range of mobility options. bp CEO Bernard Looney said “[It has] everything in one place to meet customer convenience needs and get people where they need to be.”

Integral to the hub is Jelbi – an app that integrates all Berlin’s public and shared mobility options into a one-stop-shop. “With Jelbi we offer all forms of shared mobility in Berlin from a single source,” said Dr. Henry Widera, CIO and BVG’s Head of Information and Sales Technology. “In this way we supplement the excellent local public transport with environmentally friendly sharing offers - digitally on smartphones, physically at Jelbi stations.

Plymouth, Devon: targeting 50 mobility hubs

As with any transformational transport project, at the heart of it must lie ambition of some kind. The city of Plymouth in England’s south western county of Devon, is certainly not lacking on that front. Plymouth, population of just under 250,000, is edging towards realising its significant mobility hub programme of investment through the Transforming Cities Fund (TCF), that will “reduce congestion, improve air quality and help the city prosper by investing in infrastructure to improve public and sustainable transport connectivity on key commuter routes across the city.”

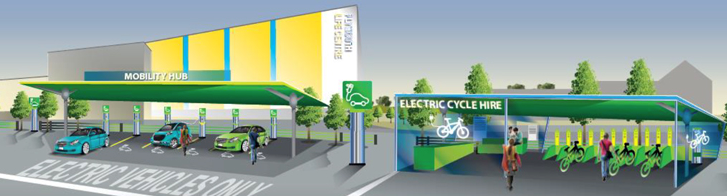

The aim is deliver 50 multi-modal Mobility Hubs across the city for both business and the public, delivering “significant carbon reductions, improved connectivity, business benefits and a sustainable, future-proofed shared transportation system,” according to official sources.

Multi-modal Mobility Hubs

The grand plan is for Plymouth’s Mobility Hubs to include: 300 EV charging points; 400 electric bikes; car club vehicles; a solar carport and secure bike parking. “The current climate, locally, nationally and globally means we require a re-evaluation of how we move, use space and travel,” says a spokesperson for the project. In addition to the aforementioned transport benefits, Plymouth’s Mobility Hubs will also “improve health and wellbeing, strengthen the economy, minimise negative environmental impact, regenerate communities and reduce poverty.”

After the three-year Transforming Cities Fund (TCF) grant period Plymouth intends to have installed in the region of 50 multi-modal Mobility Hubs, all strategically integrated into the public transport network. Local residents, employees, businesses and visitors to the city, with a rich naval history, will be able to plan their journeys to use public and shared transport modes, both in the city and on the main routes into the counties of Devon and Cornwall.

The Mobility Hub network project meets the aims of the TCF through the provision of low carbon shared transportation and new charging infrastructure connecting the region's two TCF corridors, increasing connectivity to key employment markets, education, health and leisure facilities, and services. It aligns with the policies contained within the Department for Transport's Road to Zero Strategy 2018, which specifically details the crucial role of charging facilities in meeting the Strategy's objectives.

London: mini-hub giving back to the community

CoMoUK’s exacting standards will ensure that, in the UK at least, mobility hubs all comply with a set of comprehensive regulations. However, the size and scale of the project is, in this instance, immaterial. In contrast to Plymouth’s boldly ambitious plans, in June of this year the UK's first accredited mobility hub launched in the London of Redbridge, to the east of the city in South Woodford. The mini-hub has reclaimed an on-street car parking space with dual aims of both connecting the area and aiding the environment. The hub features an electric car club bay, a community-led café with outdoor seating, and a fast electric vehicle (EV) charger. Europcar Mobility Group’s car-sharing brand, Ubeeqo, provides the two Renault Zoe electric cars associated with the space. Yes, it’s only one car parking space that has been given back to the community but, as the saying goes, Rome wasn’t built in a day – and neither was South Woodford.

Amsterdam – the affordable alternative to the private car

The cycling city of Amsterdam is in the throes of conducting experiments on the impact of new technologies on mobility. Realising eHUBS in close cooperation with local residents is one such solution. Amsterdam, says the eHUBS project, is operating a bottom-up approach and will focus on first mile of travel. Tijs Roelofs, head of innovation at the City of Amsterdam, says that the short-term goal is to increase the city’s percentage of shared cars from 5 to 30, with the long-term goal that sharing cars among neighbourhoods becomes the norm.

Amsterdam will cooperate with commercial transport providers and will build 15-20 eHUBS in a targeted area and will provide space for the commercial shared e-mobility providers.

A pilot scheme saw Amsterdam residents give up their car for two months in exchange for travel credit that could be used for public transport, bike and car sharing and taxis. 30% of the participants chose to permanently discard their car. Insights and knowledge that the City and the University of Applied Science’s Behaviour Science department will utilise in order to get people out of their privately owned cars and into shared mobility made available through eHUBS.

Initiator Waldemar Torenstra started a e-neighbourhood hub. Together with his neighbours, he gave up his own car and now shares electric cars, bikes and cargo bikes. "If I can say goodbye to my own private car feeling, it might work for other people as well." Watch the full story >

Source header: CoMo