NEXT Mobility, Intertraffic Amsterdam’s new feature for 2026, focuses on new and alternative modes and solutions that are designed to make our cities more liveable, accessible, and sustainable.

With its bold ideas to tackle challenges and drive real change, NEXT Mobility will have its own dedicated hall, with a demo area and content stage in order that solution providers can shine the spotlight on what makes them truly next-gen.

Among the range of solutions on offer in the Next Mobility space are Mobility Hubs – Intertraffic takes a look at how cities across Europe are racing to rewire the way people move.

Mobility hubs are compact, well-designed places where public transport, bike- and scooter-share, car-share, charging, micro-logistics and passenger information converge to make door-to-door trips easier without the need for a private car.

Some European cities are doing a whole lot more that simply placing a bike rack next to a bus stop

Some European cities are simply placing a bike rack next to a bus stop, while others are doing a whole lot more - integrating services, data and policy to make these hubs genuinely useful.

Amsterdam: Systems thinking and large pilots

Amsterdam rolls out station-based and kerbside mobility hubs as part of a wider shared-mobility network. (Credit: Future Mobility Network)

Amsterdam has been an early mover in rolling out mobility hubs into a coherent shared-mobility strategy. The city participates in several EU pilots (for example eHUBS) and has been actively expanding station-based and floating offerings for bikes, mopeds and cars while testing hubs in underground parking and near transit interchanges. That blend of operational scale, experimentation and policy alignment - treating hubs as part of a network rather than isolated pilots - puts Amsterdam among the most advanced on the continent.

That blend of operational scale, experimentation and policy alignment - treating hubs as part of a network rather than isolated pilots - puts Amsterdam among the most advanced on the continent.

Amsterdam’s pilot hubs (e.g., Buiksloterham, Zuidas, and Sloterdijk) follow a three-layer design logic:

- Base layer – multimodal access: bike-share, e-mopeds, car-share, and electric charging bays arranged radially around public transport nodes. Shared modes are prioritised in visibility and proximity to exits.

- Middle layer – digital & service infrastructure: dynamic signage, open data feeds, QR codes linking to apps, and integrated ticketing kiosks.

- Top layer – placemaking: green roofs, sheltered seating, and integration with retail or cafés to create a “destination” rather than a sterile transport node.

The city has even experimented with underground “mobility basements” beneath new residential blocks, consolidating car-share, cargo-bike storage, and parcel lockers to reclaim street space above for walking and greenery. These are complemented by “light hubs” - small-scale kerbside installations featuring bike racks, shared scooters, and solar-powered lockers, extending network reach into neighbourhoods.

Key design features:

- Modular construction for relocation or scaling.

- Open API for operator integration.

- Night-time lighting and wayfinding designed with accessibility experts.

Helsinki: A digital-first approach (MaaS + living lab)

Helsinki proves that modest hubs become powerful when MaaS, real-time info and ergonomics are integrated. (Credit: SOLMU project)

Helsinki’s strength is digital integration. It helped incubate Whim and other Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platforms that unify journey planning, booking and payment across modes - an essential ingredient to make mobility hubs feel seamless to users. Coupled with an active “testbed” culture where new services are trialled in the real city, Helsinki demonstrates how strong digital back-ends multiply the value of physical hubs.

In Helsinki, many hubs look modest - a few bike docks and charging points - yet their digital signage, intuitive layout and MaaS integration make them feel coherent

In Helsinki, many hubs look modest and understated - a few bike docks and charging points - yet their digital signage, intuitive layout and MaaS integration make them feel coherent. For example, at the Pasila and Kalasatama hubs:

- Real-time travel boards display tram, metro, bus, and shared-mobility availability in a single interface.

- Universal QR codes allow users to book any mode (Whim, HSL app, or private operator) without app clutter.

- Cold-climate design: heated shelter floors and anti-slip materials ensure year-round usability - a crucial consideration in Nordic climates.

- Data kiosks provide information on CO₂ savings and occupancy, reinforcing behavioural nudges toward sustainable transport.

Design takeaway: Helsinki proves that a hub doesn’t need grandeur; thoughtful digital and ergonomic design can make small spaces highly effective.

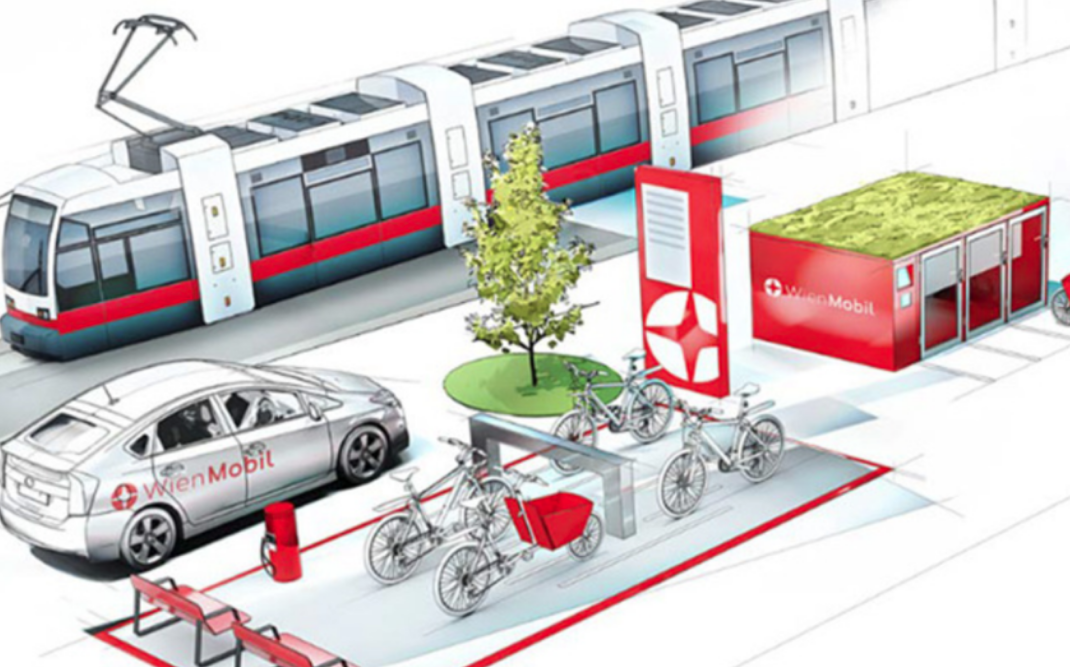

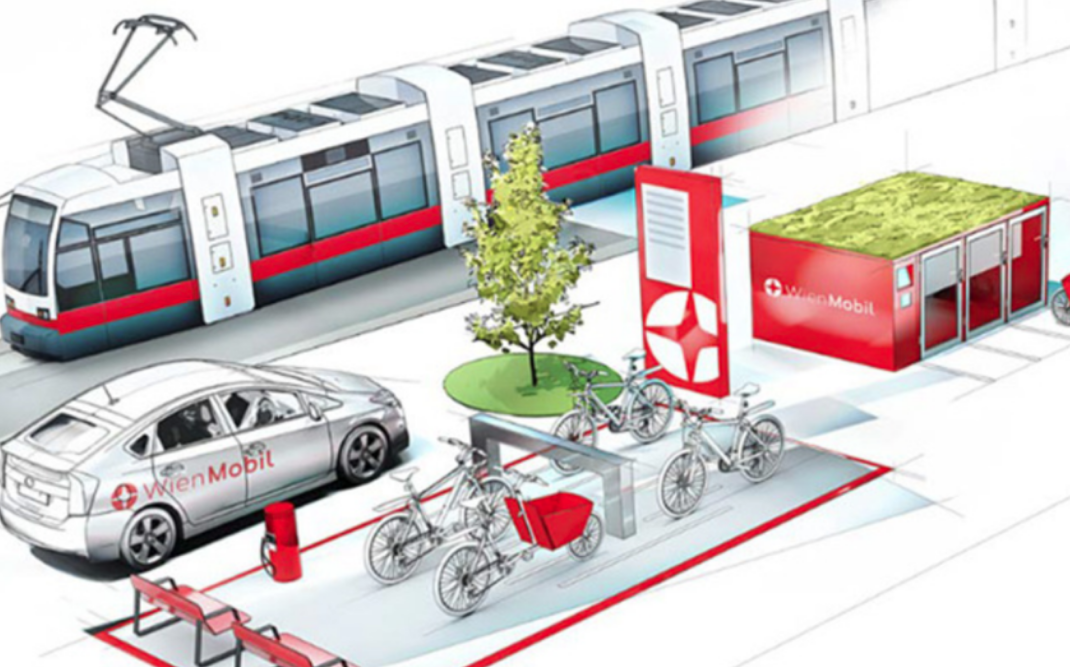

Vienna: Branding, operations and inclusivity

Vienna integrates mobility hubs into its WienMobil brand for city-wide recognisability and inclusive access. (Credit: City of Vienna)

Vienna treats hubs as part of a customer-facing mobility brand (WienMobil) and integrates car- and bike-sharing with excellent transit connections and passenger facilities. Vienna’s emphasis on wayfinding, inclusive access and municipal operation/coordination - not leaving hubs solely to private operators - is a model for reliability and broad public adoption. That operational focus helps Vienna convert infrastructure into sustained behaviour change.

Vienna treats hubs as part of a customer-facing mobility brand and integrates car- and bike-sharing with excellent transit connections and passenger facilities.

Vienna’s WienMobil-Stationen are textbook examples of integrated, municipal-run mobility hubs. Located in residential districts like Simmering and Kagran, each hub typically includes:

- Bikeshare and car-share spaces with e-charging infrastructure.

- Cargo-bike lending and parcel lockers, facilitating local logistics and community use.

- Rain-protected seating, greenery, and tactile paving, prioritising accessibility and comfort.

- Clear WienMobil branding and consistent signage for instant recognisability city-wide.

Vienna also introduced “Mobility Points Light” - smaller modules focusing on bike and scooter sharing near tram stops. Both types share a design language and colour scheme, reinforcing brand trust and user familiarity.

Design philosophy: Vienna treats hubs as public infrastructure, not private concessions, ensuring cohesive aesthetics and equitable access across all districts.

Copenhagen: Living labs and regional coordination

Copenhagen links living labs to regional roll-out so hubs can be replicated quickly. (Credit: Gemini)

Greater Copenhagen is notable for its regional, research-driven approach: innovation hubs and living labs tie municipalities, universities and industry together to trial multimodal hub concepts in peri-urban and suburban contexts. The city’s strength is rigorous evaluation alongside pilot deployment, which helps scale the right solutions across different urban geographies.

• Copenhagen’s “Repro-Mobility Hub” and “Danish Living Lab” pilots test how hubs can thrive beyond dense urban cores:

- Flexible micro-hubs at suburban train stations combine e-bikes, car-share, and EV charging with modular solar canopies.

- Wayfinding pylons use clear pictograms and LED lighting visible from 100 m, guiding first-time users.

- Integrated stormwater management (green swales and permeable paving) doubles as sustainable drainage infrastructure.

- Plug-and-play modules allow municipalities to reconfigure layouts as demand evolves.

By designing with adaptability in mind, Copenhagen ensures that hubs can be scaled or replicated quickly throughout the region without custom builds each time.

Design philosophy: By designing with adaptability in mind, Copenhagen ensures that hubs can be scaled or replicated quickly throughout the region without custom builds each time.

Barcelona: Urban redesign that amplifies hubs (pic5)

Barcelona’s superblocks and tactical urbanism create fertile demand for neighbourhood mobility hubs. (Credit: Urban Platform)

Barcelona’s superblocks (superilles) and aggressive micromobility strategy have reshaped streets to favour walking, cycling and shared modes. While not every superblock contains a “mobility hub” in the classical sense, the city’s deliberate reduction of car dominance creates fertile demand and space for hubs to function effectively - especially for last-mile solutions like Bicing (bike-share) and e-cargo pilots. Barcelona shows the power of pairing street-level urbanism with mobility provisioning.

In Barcelona, mobility hubs are interwoven into the superblocks. Typical features at hubs in Poblenou or Sant Antoni include:

- Bike-share stations paired with e-scooter docks and parcel pick-up lockers.

- Solar-powered charging benches and canopy seating that encourage ‘dwell time’.

- Civic art and micro-parks co-located with mobility infrastructure to soften the visual impact.

- Tactical urbanism materials (painted asphalt, planters, modular bollards) that can be adjusted as patterns of use evolve.

These hubs are designed less as transit nodes and more as “mobility plazas”, where sustainable transport, community gathering and street life coexist. This is a distinctive Mediterranean interpretation of the mobility-hub idea.

While not every superblock contains a “mobility hub” in the classical sense, the city’s deliberate reduction of car dominance creates fertile demand and space for hubs to function effectively

Strong runner-up

Bremen and Hamburg pioneered small, pragmatic mobility points that could be replicated city-wide. (Credit: City of Bremen)

Bremen & Hamburg: Early practical pioneers in co-locating carshare and bikeshare with transit; their pragmatic, transport-first designs influenced many later European hubs. Bremen’s mobil.punkt and Hamburg’s Switchh points illustrate Germany’s pragmatic approach:

- Compact footprint (under 200m²) enabling installation in tight urban corners.

- Adjacent to tram or bus stops, eliminating last-metre detours.

- Unified ticketing via city transit cards and consistent branding.

- E-vehicle charging infrastructure integrated neatly into curbs, avoiding clutter.

These designs prioritise efficiency and functional clarity over aesthetic experimentation - a strategy that has made them easy to scale and replicate across German cities.

What makes a city “progressive” on mobility hubs?

From the examples above, five attributes repeatedly distinguish the leaders:

- Network thinking - progressive cities plan hubs as part of a connected system, not as one-off showcases. Amsterdam and several Dutch pilots explicitly pursue hub networks

- Digital integration - MaaS platforms, unified ticketing and real-time data turn physical proximity into frictionless travel (Helsinki’s approach).

- Operational coordination - municipal coordination or strong public-private governance prevents fragmentation and ensures reliability (Vienna).

- Place and street design - reallocating space from cars to people (Barcelona superblocks) amplifies hub effectiveness by lowering car convenience and increasing demand for alternatives.

- Evaluation and scaling - living labs and research projects (Copenhagen, SmartHubs/EIT projects) help identify what scales and what does not.

Common pitfalls to avoid

- Good infrastructure = success: Physical infrastructure without service reliability, pricing incentives or easy payments often fails to attract regular users. The SmartHubs project has highlighted this “gap” across many European pilots.

- Operator fragmentation: If too many providers operate without interoperability (different apps, charging standards, docking rules), user experience suffers. Paris and others have been actively working on operator-neutral charging and standards to tackle this.

Practical takeaways for cities that want to catch up

- Start with a high-value node - pick transit interchanges or neighbourhood centres with strong footfall to pilot a hub.

- Bundle service + payment + wayfinding - users must see the hub as one service, not many. Integrate payments and apps early.

- Design streets for people - make walking and cycling at the hub convenient and safe; remove through-traffic where possible.

- Measure and iterate - collect user data, run living-lab pilots, and be ready to reconfigure offers (e-bikes versus cargo bikes versus chargers) based on uptake.

Final thought

There’s no single “right” mobility-hub blueprint - the most progressive European cities combine policy, digital infrastructure, and urban design so those three layers amplify and complement one another. Amsterdam, Helsinki, Vienna, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Bremen and Hamburg, to name but seven cities, each show different paths to the same end: making sustainable, multimodal travel easier than driving. For cities starting today, the message is clear - don’t just build a dock or a charger; build the experience, the data plumbing and the street around it.

There’s no single “right” mobility-hub blueprint - the most progressive European cities combine policy, digital infrastructure, and urban design so those three layers amplify and complement one another

Europe’s most forward-thinking cities are redefining mobility hubs as adaptable, human-centred infrastructure. Their success rests not only on technical sophistication, but on design empathy, understanding that people choose sustainable transport when it’s visible, intuitive, comfortable, and beautifully woven into the life of the city.

.png?h=183&iar=0&w=290)